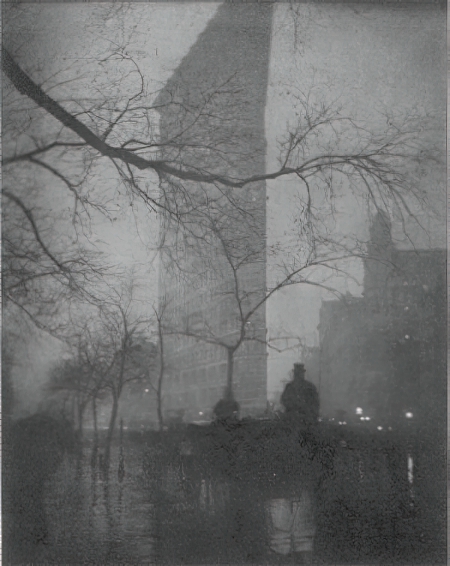

THE CHARM and wonder of street photography derives from the fact that it is, more than anything else, a celebration of humankind as we navigate the pressure-cooker conundrums of metropolitan life.

The ethos and the aesthetics of street photography have changed little from the earliest days, nor should they: in its purest form, street photography is simply life on the street and life on the street is pretty much the same in cities all around the world, although shooting pictures on the street in New York City or Paris is very different from shooting in, say, Dallas or Orderville, Utah, due to cultural acceptance of candid photography and/or population density. Nonetheless, street photography at its core has changed little from the days of the daguerrotype.

Hey Babe, take a walk on the wild side.—Lou Reed

Herewith an article I wrote for iPhotographer Magazine. Most of you know that I asked six well-known iPhone street photographers if they would like to be featured in the PIXELS book. One demanded an exorbitant fee and the other five never bothered to respond despite several polite and respectful emails. I was trying to be nice in this article.

iPhonic street photography has been the perfect condensed microcosm of all that is encompassed by the fascinating rise of iPhone photography in this era of instant global sharing: the discovery and awakening of creative energy and aspirations in millions around the world, the building of communities and shared delights, counterbalanced by cleverness often trumping composition, the clash of the clueless and egos unbounded, and all the other tempestuous and tawdry tendencies that have plagued art movements since time immemorial.

There is little law and much passion in these territories, my brothers, forever generating bulbous cumulae of persistent drama and wonder, so keep your whiskey close and your powder dry.

Any student of photography will not be surprised to hear that the early years of iPhone photography online were absolutely dominated by street photographers in the USA and Europe. Street photographers have always been a breed apart, most of them, and the rise of mobile phone photography, combined with the ability to share instantly, was perfectly suited to the community’s historical ethos.

Pioneers Sion Fullana, Greg Schmigel, Jordi Pou, Star Rush, Oliver Lang, Marco La Civita, Valerie Ardini, Aik Beng Chia, Misho Baranovic, Dominique Jost were joined later by photographers like Roger Clay, Alon Goldsmith and too many to name here in creating quite memorable images as part of the huge, vibrant communities on Flickr and elsewhere across the pre-Instagram internet.

Beyond Flickr, Eyeem has remained the spiritual home to most street photographers, and many of whom have become very well-known within the greater worlds of art and photography over the past few years. Of course, everybody seems to be on Instagram now.

Another site dedicated to promoting iPhonic street photography via gallery shows popped up in Spain in late 2010: eyephoneography.com, founded by Marco La Civita and Rocio Nogales. They have produced a number of well-done gallery shows, usually focussing on the work of only four or five photographers at a time. Their ability in promoting the work to the general public throughout Europe has been unparalleled, with well-curated, beautiful exhibits and amazing press coverage. They are still very active, and a recent show has been moving for some time from country to country to great reception.

The development and evolution of iPhonic street photography has been as tumultuous as that of any art movement in history. As a good friend of mine once said,”You want a knife-fight? Put two poets in a room.” That applies in spades to realm of iPhone photography.

Indeed, the first eyephoneography show in 2010 at the Madrid Hub Art facility was destroyed by vandals, apparently some photographers who were violently jealous of the amount of attention the gallery show featuring the new medium, i.e., iPhonic imagery, was getting.

In 2011, a group of the foremost and best-known “mobile street photographers,” as they called themselves, formed an ambitious collective, The Mobile Photo Group, aka MPG, and built a well-promoted website featuring their works, along with dense biographies and verbose personal mission statements.

Internal strife, artistic egos, and an inability to define exactly what the purpose, beyond self-appointed exclusivity, of what the club was led to a rapid and ugly disintegration of the group and the website within mere months of its founding.

Art history is replete with such fragmentation and acrimony. Indeed, I remember vividly the day, in August of 2011, where it dawned on me that the global iPhone photographic community was as crazy as could be found in any art movement in history: that was the day my belief in the validity of the medium was confirmed.

Street Photography As Performance Art

Renowned street photographer Joel Meyerowitz said, when interviewed by curator and historian Colin Westerbeck (with whom he co-authored a definitive book on street photography, “Bystander: A History Of Street Photography.”),

“At the same time, though, you knew it was beautiful, because ‘tough’ also meant that—it meant beautiful too. If you said of a photograph, “Gee, that’s tough” or “that’s beautiful”, it meant that in the moment of making that photograph, you were beautiful. It was as if you were graced at that moment. You were in touch with the sudden appearance of beauty and were touched by its purity.”

Implicit in this conceit is the idea that the act of taking the picture is as important as the picture itself. Some love this and all that it implies. I do not count myself among them.

Street photography, for many in the iphonic realm therein, seems to be a form of performance art or street theater, very much about process and the act of shooting. The resulting image is, thererfore often completely disposable, is posted and the photographer moves quickly to the next one.

Reminiscent of “action painter” Jackson Pollock hurling paint, we must at times endure the “action photographers” in our midst. Let us not forget Andy Warhol’s response to Pollock: his copper-painted canvases upon which he had his friends urinate to make bold splattered patterns of oxidation and multi-hued metallic corrosion. Andy, we salute thee!

The abscence of curation has at times created rather embarrassing moments in our history, as when a well-known site had a photo contest with a “Nature” theme. The winning image was a pond in a city park with apparently unnoticed cigaret butts floating in the lower left corner. It did not reflect well on our efforts for acceptance in the art/photography world.

Luckily, the medium has matured and developed across the board to an astonishing degree in these few short intervening years.

the battle for the soul of the medium

With the ascendance of iPhone photography and the early attention it was getting, came the swarming arrival of “real” photographers to the movement, who brought with them the bain of modern art photography, at least in the hands of the mediocre: computer editing of images. which was about as welcome as a herpes outbreak at a swinger convention.

A battle raged online within the community, on Facebook, Twitter, public forums for most of 2010 in an effort to define what the medium was: a subset of photography where Photoshop usage on desk and laptop computers was allowed, or was the medium to be defined by the device itself? The argument was settled, finally, when Apple sent out a press release in August of 2010 which stated: “Iphoneography is an art form inspired by, shot with, and processed on the iPhone.”

I suppose, in the interest of reportorial transparency, I should note that it was mostly me and bloggers, Glyn Evans of iphoneography.com and Marty Yawnick of lifeinlofi.com on one side against everybody else, mostly from the existing street-photo community. Needless to say, this was a very important battle in the evolution of the whole medium of iPhone photography and I’m very glad we prevailed in the end. With the rise of Instagram, for most, the debate is almost moot, now. But at the time …

Curiously, uncurated iPhone photo gallery sites EyeEm and Iphoneart.com continued to allow computer-edited images on their sites. EyeEm’s explanation was that they “only cared about the ‘decisive moment,” referring to Cartier-Bresson’s oft-quoted and almost as often misunderstood phrase.

The Decisive Moment

Cartier-Bresson usually captured a number of “decisive moments” as he stalked his target: on his contact sheets one can clearly see the sequence as he moved in for the perfect shot.

He often made his lab assistants work for a week to extract the perfect print out of the perfect negative: that is old-school apping. I am certain to my core that, were he alive today, Cartier-Bresson would be a huge photo-apper and mere desaturation would never suffice: he was a painter at heart and gave up photography in his last years to spend his time with a sketch pad in his hands. I have more than once envisioned the master falling asleeping hunched over his iPhone apping a picture, as so many of us do in the grip of the obsession.

Early iPhone street photographers dealt with the extreme limitations of the iPhone camera itself: low resolution, unable to deal with bright light or dark low-lights, an optical sensor in place of a lens, and the most difficult challenge of all: the quarter-to-half-second lag that often occurred between the lifting of one’s finger off the shutter button and the actual snapping of the picture. If you are shooting a sleeping cat or a bowl of fruit, this is not an issue, but if you are shooting someone jumping over a puddle, it’s an eternity. This was not fixed until the iPhone 4.

Pioneering iPhonic street photographer, Greg Schmigel once said, “There’s something special and unique about shooting street photography. It’s real, it’s true slices of life as we see it, and many times, slices of life as the rest of us miss them.”

This sums up the best and the highest ethos of the passionate street photographers wandering the naked and vibrating streets, capturing and sharing the vast waking electric dream with the rest of us.

Welcome to electric avenue!

Leave a Reply